By Kathryn B. Creedy

A little noticed trend is happening in America as state and local economic and workforce development officials identify aviation and aerospace as a key economic drivers. In response they are quickly developing the workforce these future employers will need.

So, it was absolutely no surprise I learned the same was happening in the Caribbean where Captain Alicia Hackshaw, a flight operations inspector for the Trinidad and Tobago Civil Aviation Authority, is urging governments to develop Free Trade Zones (FTZ) and Special Economic Zones (SEZ) to attract aviation and aerospace trainers and manufacturers. She hails from Trinidad and Tobago, a small island just off the coast of South America.

“I saw the global demand for pilots, technicians, engineers, and rotorcraft operators continuing to rise, and realized the Caribbean was sitting on untapped potential,” Hackshaw explained of her grand vision to transform the Caribbean economy.

Diversifying the Economy

Hackshaw’s ambitions are not far off the mark given efforts over the last 20 years in Florida to diversify its tourist-based economy. Florida pairs its highly educated workforce and its life-in-paradise vibe to attract and retain both businesses and provide jobs for its workforce.

Once reliant on tourism and launches from Kennedy Space Center and the Cape Canaveral Space Force station, the state was devastated by the shutdown of the Shuttle program. Since then, it has been extremely successful and now has a robust multi-disciplinary economy that includes, financial services, banking, higher education, health, research and development, manufacturing and aerospace and aviation. Orlando is now the center for simulation technology in various industries and Florida’s universities partner with aviation and aerospace companies and other industries to produce cutting edge research and development.

Efforts on the Space Coast alone turned the area into a manufacturing hub with the likes of Embraer Executive Jets, Blue Origin, SpaceX and ULA, complimenting operations by the big defense and aerospace primes – Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, Collins Aerospace, GE Aerospace and Boeing. Dassault is opening a maintenance and service center in Melbourne.

For me, perhaps the poster child of this type of economic activity is deep in coal country – West Virginia, which identified aviation/aerospace as a key economic driver even though it only had a small footprint in the industry. It launched an aviation program at Marshall University and partnered with airports to develop both pilot and aviation maintenance training. Community colleges now have aviation in the curricula.

Its efforts paid off. Pratt & Whitney picked Bridgeport, WV, for its assembly and test center for Pratt & Whiney Canada engines for the U.S. Department of Defense. The service center overhauls and repairs turboprop and turbofan engines and components manufactured by Pratt & Whitney Canada. It is now a Center of Excellence for corporate turbofan and turboprop engines. When you consider that aviation maintenance technicians are paid $65,000 in their first year and can make $120,000+ after five years it is little wonder states are zeroing in on maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO).

Ohio, Michigan, Colorado, Pennsylvania and others have all developed aviation/aerospace education programs to begin to build a high school to career pipeline for manufacturers, MROs, airlines and business aviation companies. Recently, Michigan launched the Michigan Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) Initiative, designed to scale Michigan’s AAM capabilities, ensure safe and efficient integration of these technologies across public and private sectors, and position its workforce and manufacturers as national assets to attract business. Ohio, already heavily geared toward aviation, space and defense, did something similar a few years ago and bagged a Joby manufacturing facility.

The point is clear — investing in education and the workforce — works.

Brain Drain

In conversations at CaribAvia 2025, it was clear the region suffers from the same brain drain experienced in so many “remote” places as youngsters seek their fortunes and future lives in Europe, the US and Canada.

“We’re exporting our future,” Hackshaw, who is also on the board of the Trinidad and Tobago Trade and Investment Promotion Agency (TTTIPA), explained. “Many students from the Caribbean go abroad for education, some as early as secondary school. For aviation, training abroad can cost USD$100,000 – USD$150,000. Even non-aviation programs cost USD$25,000 – USD$40,000 per year. Institutions like Trinidad’s University of Trinidad and Tobago (UTT) and Guyana’s technician school prove we can train our people here. We just need to support and expand those models instead of subsidizing other countries’ economies with our talent.”

Creating an indigenous training and manufacturing capacity is what energizes Hackshaw.

In tallying the current aviation footprint in the region, Hackshaw noted the aviation sector contributes $2.5 billion (1.4%) to GDP in the Caribbean region including $1.3 billion from airlines, airports and ground services; $0.7 billion indirect through the aviation sector’s supply chain; and $0.6 billion contributed by employee spending in local economies. The sector supports 1.6 million jobs directly and indirectly, spanning airlines, airports, ground services, tourism, training, and logistics sectors, all of which driving regional economic growth.

“We already have wins to build on such as the UTT which offers programs like the Certificate in Aviation Technology and the BSc in Aeronautical and Airworthiness Engineering (AAE),” the former helicopter pilot for Bristow Helicopters told Future Aviation/Aerospace Workforce News. “UTT even provides a direct hiring stream into Caribbean Airlines, which is a great advantage. There’s also Guyana’s tech school, Suriname’s growth, Punta Cana’s new MRO hub.

“Another exciting enabler is the rise of Special Economic Zones (SEZs),” she continued. “These zones attract investors by offering fiscal incentives, simplified regulatory processes, and targeted infrastructure. Trinidad and Tobago recently passed SEZ legislation, and aviation should absolutely be prioritized within that framework. Now we need a cohesive strategy and public-private alignment to make aviation a pillar of regional development. I’m committed to helping any Caribbean government develop their aviation sector—through roadmaps, PPP structuring, training strategies or manufacturing pilot programs. We already have the raw materials: smart students, committed professionals, quiet success stories. Now we need to build the system that allows those pieces to fly—literally and figuratively. “

Hackshaw wants governments to adopt the public-private partnership (PPP) model where government creates the framework, and industry and education deliver solutions.

“We need scalable, sustainable infrastructure…and PPPs are how we get there,” she told CaribAvia 2025 participants. “This effort was entirely led by industry, and by people like me who couldn’t wait for policy to catch up with reality. I saw the global demand for pilots, technicians, engineers, and rotorcraft operators continuing to rise, and realized the Caribbean was sitting on untapped potential. We can’t wait for government to lead. We need to build from within, then invite government to join the journey.”

Industry Led Effort

Her ace in the whole is the fact that industry is helping her lead the charge. Hackshaw developed a Caribbean Aviation Roadmap, a strategy for regional aviation growth starting with flight training, maintenance education, and expanding into aviation and aerospace manufacturing, helicopter operations, and drone systems. The contribution of developing training organizations would have a triple impact on the economy by creating jobs and skill development, attracting international trainees and driving local employment, global partnerships and investments.

CaribAvia Themes Offer Many Economic Development Ideas

The idea has been core to CaribAvia since its founding. In recent years speakers from around the world indicated the Caribbean could be instrumental in its own economic development by identifying the training and manufacturing needs and developing programs in response. Given the competition between the different Caribbean states, the effort requires a Carib-wide effort to identify islands that would specialize in development of workforce education programs for each of the disciplines – maintenance, drone, advanced air mobility, pilot training, aviation maintenance training – divvying them up amongst the islands so everyone can benefit.

As for manufacturing, Hackshaw pointed to the projected growth of both MRO and manufacturing with North America the largest component. The numbers in the global industry put the $1-2 billion economic contribution of aviation in the Caribbean provides a peek at what could be in the region.

The global aerospace manufacturing market was valued at USD$412 billion in 2023 and is expected to surpass $550 billion by 2030, driven by rising demand in commercial, military, and general aviation sectors. The goal is to attract high-tech foreign direct investment while diversifying beyond the economically sensative tourism model.

She also pointed to the growing aviation manufacturing and MRO sectors in Puerto Rico and Morocco as well as the impressive impact of Mexico’s aviation manufacturing industry, saying aerospace is a top export sector for countries like Canada, Mexico, and Morocco. Beyond the tourism jobs created by airline service in the Caribbean, the region could follow Mexico where aviation/aerospace supports 60,000 jobs in Mexico and contributes significantly to economic growth and technological advancement. Turning to the impact of attracting manufacturing companies, she noted they offered high-paying jobs and STEM growth, adding the sector provides wages 2 to 4 times above regional averages and promotes STEM education, fostering a skilled workforce and suggested its free-trade zones could be an advantage in the age of tariffs.

Developing, Not Exploiting, Human Capital

“It’s all about human capital development,” she said, pointing to the number one problem across the aviation/aerospace ecosystem. “The groundwork includes feasibility studies, policy alignment, and investment planning—all geared toward positioning the Caribbean as a hub for aviation human capital development.”

In providing the framework for the Caribbean Aviation Roadmap, governments would be doing more to lift residents out of the minimum wage jobs characterized by tourism and adapting to the high-tech future of most businesses.

“It’s no longer just an aviation issue—it’s an economic development issue,” said Hackshaw. The government is now beginning to lean in more, recognizing aviation as a strategic industry that can drive diversification beyond oil and gas. While Trinidad and Tobago for me is the launchpad, the vision is unapologetically Caribbean. We can’t afford to think in silos anymore. The region needs an integrated aviation and aerospace strategy that trains talent, supports business, and keeps our best and brightest from emigrating.”

Hackshaw also touched upon another CaribAvia theme — improving regional connectivity especially with the advent of advanced air mobility, ideally suited for fast, convenient island hopping.

“My vision is a Caribbean Aviation and Aerospace Corridor, a cooperative model where each country contributes its strengths,” Hackshaw explained. “Trinidad may specialize in flight and maintenance training; Barbados in logistics; Antigua in certification; Guyana and Suriname in advanced UAV systems or manufacturing. It’s a federation model rooted in shared purpose and mutual benefit.”

Hackshaw cited the new aircraft maintenance center in Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, built by Lithuania-based FL Technics US$50 million project that includes a logistics hub and aviation training academy. The idea is to provide service closer to its customer base. The goal is creating jobs, retaining talent, and boosting the national economy.

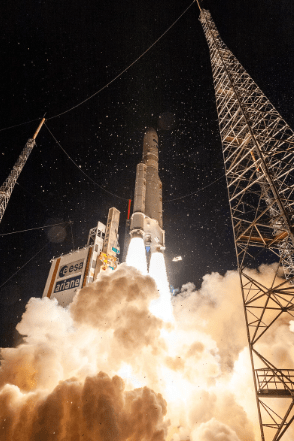

In addition, she pointed to Guyana’s Art Williams & Harry Wendt Aeronautical Engineering School, already producing high-quality aviation technicians, directly supporting Guyana’s growing aviation and energy needs. While she did not mention aerospace, it cannot be missed that the European Space Agency developed a seasoned and lucrative Spaceport in French Guiana. She concluded by saying Suriname’s booming economy is opening up real opportunities for regional air support, logistics, and helicopter operations.

“These are real models from which we can learn and expand on together,” she said turning to her home country. “Trinidad and Tobago is at a pivotal moment in its economy and I am envisioning a new era in its aviation development story. The country needs to make deliberate moves to revamp and expand its aviation training infrastructure with a vision that’s both national and regional in scope. I would like to work with interested parties to establish a comprehensive aviation and aerospace education and training ecosystem—from flight training and aircraft maintenance to aviation management and even entry-level exposure for secondary school students. The idea is to create a pipeline of skilled professionals who are trained locally and ready for both regional and international markets.”

Hackshaw estimated the funding needed to develop a flight training academy would be between $8 and $12 million while a maintenance school would require $4 to $10 million. However, for an aviation manufacturing incubator hub for UAVs, rotorcraft parts and interior kits, the cost would be between $2 and $4 million.

“These are small investments with big returns – especially through a PPP model, where government and industry share responsibility and reward,” she explained. “You don’t have to build a Boeing plant to enter aerospace, you can start with components, support systems, and regional needs.”

Pathway to Prosperity

Hackshaw is also intent on developing aviation STEM academies and certified training organizations with partnerships with global leaders in aerospace training.

Her vision is in its infancy although she has already engaged aviation educators, private investors, diaspora professionals, international flight schools, and regulators who see the long-term value.

“To truly scale, we need governments to come to the table through structured PPPs,” she said. “I’ve seen strong interest from many individuals, but only Antigua’s Aviation Minister has taken tangible steps to engage. I’m hopeful that more governments will follow the examples set by Guyana, Suriname, and the Dominican Republic, who are already investing in real infrastructure. We need people and organizations who see the Caribbean as more than a vacation destination, and who understand that aviation is a pathway to prosperity. We want partners who understand that this is not a charity case – it’s a smart investment in a region with young talent, favorable geography, and untapped potential.

“We are looking for those who can offer technical expertise, accredited training, and mentorship pathways, and who are willing to build institutional capacity rather than just deliver a product or service,” she explained. “The region also needs partners willing to help us tell the story and advocate with us at the policy and investment level. We believe strongly in public-private partnerships as the vehicle for development. We need public leadership, but we also need private efficiency, international certification standards, and a commitment to training, hiring, and building locally and I stand ready to serve as an aviation advisor to any nation that wants to develop the aviation sector, whether through technical policy guidance, PPP structuring, or infrastructure planning. This is about building a legacy for the region.”

Barriers

The response to her efforts to spread the vision throughout the Caribbean is hopeful. “The reaction remains overwhelmingly positive, especially when people hear how this vision includes helicopters, UAVs, training, MRO and manufacturing,” said Hackshaw. “They’re not used to hearing the Caribbean in that context and when they do, they start asking the right questions. We recognize the value of the vision, and there’s a strong emotional response when they hear how aviation could unlock prosperity in the region. It’s not the idea that’s hard, it’s the execution. And that’s why we need committed partnerships and political courage.”

She sees many barriers not the least of which is the insulated outlook of regional governments.

“That’s the elephant in the room, isn’t it,” she asked. “Fragmentation has been the region’s Achilles’ heel. But I believe the aviation sector offers a unique opportunity to turn that around. It’s in every country’s interest to collaborate – no one island can do it alone. Aviation infrastructure is too expensive and talent too mobile.

She also raised the prospect of a single Caribbean sky, one of the main goals of the annual CaribAvia conference.

“I would love to advocate for aviation to be prioritized under the CARICOM Single Market & Economy (CSME) framework,” she said. “Regionalism often sounds great in speeches, but in aviation, where cross-border thinking is essential, it’s been lacking. Regional governments have not yet taken a lead on aviation or aerospace development so we will have to do it ourselves. I’m working hard on forming a network of professionals, educators, and investors who are willing to build across borders, led by the private sector.”

Captain Hackshaw knows every long journey starts with the first step and may take time. But it will be worth the effort to prevent the brain drain now occurring and build a more robust economic future in the region.